Frequent Disturbances Increased the Resilience of Past Populations

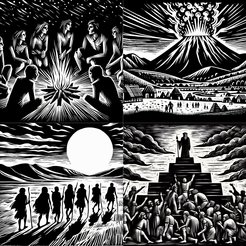

Researchers analyzed evidence of global population change spanning 30,000 years to uncover the impact of disturbances on humans and the factors affecting their resilience.

Disturbances play an important role in human population growth by enhancing the resilience of survivor populations throughout history, new research has found.

The research, published in Nature, looked at how quickly past populations recovered after disturbances – including extreme events such as volcanic eruptions, warfare, the impact of colonialism, and aridification, among others – and what factors affected their ability to withstand and recover from these challenges. The study found that a single factor – how often events like this happened – increased both the ability to withstand and to recover from them.

Lead author Dr. Philip Riris, Senior Lecturer in Archaeological and Paleoenvironmental Modelling at Bournemouth University, says: “We think that experiencing a disturbance leads to a population experiencing some sort of learning as a result, which led to being more prepared the next time.”

In addition, the findings showed that these frequent population disturbances paradoxically helped to maintain constant long-term growth rates – suggesting that temporary or relatively local declines are a fundamental feature of humans’ long-term global success.

“It could also be that those with pre-existing technologies, adaptations, and social structures that were useful when a disturbance hit were better able to weather it, while others weren't, eventually shaping the cultural system towards those resilient traits,” Riris adds.

Population crashes and recoveries in the past lasted for decades or centuries, with disturbances lasting a median average of 98 years – and many lasting for hundreds of years.

The research also found that the rate of disturbance was strongly influenced by land use, with heightened rates of population decline occurring in farming and herding societies. However, among the sample of populations examined by the study, these societies were also more likely to be more resilient overall.

The international team, made up of researchers from across Europe, USA, and Asia, collated and analyzed over 40,000 radiocarbon dates from existing studies and databases that featured evidence of population downturns, covering regions ranging from the Arctic to the tropics.

While research has previously studied the impact of disturbances in the present, this is the first systematic global comparison of humans’ ability to absorb and recover from disturbances through time.

"The resilience of ancient populations in the face of frequent disturbances can reveal intricate relationship between environmental pressures and human adaptation over millennia,” says Dr Yoshi Maezumi of the Max Planck Institute of Geoanthropology. “Understanding these dynamics not only enriches our comprehension of past civilizations but also offers invaluable insights into navigating contemporary challenges."

“Archaeology is uniquely suited to tackling these issues,” Riris concludes, “because nobody else looks at human societies for as long or as systematically as we do. Our paper is a landmark in terms of knowing what to expect about societies' responses to disturbances on a truly planetary, deep time scale.”